The asphalt industry is careful about adopting new materials or techniques. It has to be: people’s lives depend on the materials or techniques working as advertised. At the same time, no innovation means no improvements, which doesn’t work either. Improving pavement requires rigorously thinking through the risks of new ideas and finding the best field projects to test them.

Enter the idea of installing a highly modified Superpave mixture in one thick lift. Howard Anderson, a state asphalt engineer for Utah with more than 30 years of experience, and Lonnie Merchant, a Region 2 UDOT materials engineer, worked together to implement a UDOT thick lift project of their own in Utah. Anderson was drawn to the idea because he viewed applying two layers as a waste of time. Instead, he wanted to find a good way to do one layer without sacrificing quality. For five years, Anderson and others researched projects done elsewhere and did lab tests in Utah to solve the problems they faced.

Their goal was to reduce construction time, eliminate problems caused by multi-lift paving such as tack coat and delamination between layers, and put the asphalt down in a location that would make quality shortfalls obvious. However, the most challenging part of the project was producing high-quality asphalt with 1% air voids to achieve their goals.

Constructing stable, durable HMA depends on the pavement’s density. Compaction determines density, but the thicker the lift, the harder it is to get the correct density. In general, the asphalt industry has gotten its best results when in-place air voids are limited to a 3%-8% range. That means successful pavement with 1% air voids is something out of the ordinary. According to Anderson, normal mix designs in the U.S. are usually 4%. The Utah average is 3.5%.

What determines the specifications for most air voids? When they are below 3%, pavement tends to rut and form ripples. The ripples are also called shoving or wash-boarding. When air voids are above 8%, air and water can get into the pavement and cause cracking, oxidation, raveling, and water damage. Raveling occurs when traffic wears away aggregate particles from the asphalt cement. It indicates a poor quality mixture or asphalt hardening.

Anderson was familiar with rutting risks when air voids are below 2%. However, he also knew that binding technology had changed. Polymer-modified binders would provide a stronger glue than was available in the past, which meant going below 4% air voids was no longer an unrealistic goal. Even with the smaller air void percentage, laying quality asphalt would still be possible.

In 2016, Anderson worked with Clark Allen, a UDOT central lab technician, to run Hamburg rut tests that used 76-34 polymer modified binder instead of the standard UDOT choice, 64-34 polymer modified binder. It is two grades higher and has twice as much polymer as the standard. Allen tested binder contents of 4.8%, 5.8% and 6.8%. The results were tested with extra weight after the first test was successful. The material would not rut, and Anderson learned that when the binder content approaches 7%, the asphalt acts more like the polymer than regular asphalt. It doesn’t become sensitive to over-asphalting.

Having higher binder content minus the rutting risk meant thicker asphalt lifts could be compacted than was possible previously. Two lifts separated by a tack coat could be replaced with one lift, and the increased binder would lubricate compaction.

Anderson attended the WASHTO Conference in April 2016, held in Salt Lake City, and he presented his idea at the conference. After additional presentations, Staker Parson Materials & Construction decided to use the idea as part of a larger project. They had agreed to mill two inches off 20 miles on I-80 and replace it with two inches of stone matrix asphalt totaling 40,000 tons. A port of entry with a six-inch lift was part of the project spec.

The project site is between Nevada and Utah, and it is located in the middle of the Bonneville Salt Flats. It’s hard to imagine a more difficult place for using asphalt. Most asphalt that has been laid at this location begins having problems days after being laid. Summer temperatures are often higher than 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Winter temperatures are often below 10 degrees Fahrenheit. Heavy truck traffic headed for California ports is a day-in, day-out reality. The annual daily traffic count is 7,600 vehicles per day. Of that total, 51% are trucks.

UDOT usually uses a 12.5 mm 75 gyration mix. The binder is 5%, and the air void target is 3.5%. For the port-of-entry test strip, the recipe was different. They used a 12.5 mm 50 gyration Superpave mix. It had 15% RAP, PG76-34 binder, 0.5% Evotherm, 6% total asphalt content and 1% air voids.

The project superintendent was Mike Stevens. He and his crew at Staker Parson Materials & Construction wanted to eliminate some of the mix’s unknowns before laying the port-of-entry test strip. They decided to pave a 100-ton test strip in its pit the day before the other test strip was laid. The 100-ton test strip was useful. Staker Parson changed the rolling pattern and calibrated its equipment thanks to information gained. The mix was stiffer than the crew was used to, and they knew they would have to pave it down fast. Since the test strip retained more heat than expected, they allowed extra time for the paving to cool there and on-site.

Preparation for the paving job included having a subcontractor, Coalville’s Construction Material Recycling (CMR), mill out asphalt and concrete. The subcontractor removed three inches of asphalt and three inches of concrete. They started 300 feet ahead of the scale, ended 100 feet after the scale, and created a strip that was 14 feet wide. CMR also chipped off concrete from the scale’s metal housing and swept.

Stevens and his crew decided to prepare ahead and minimize any potential waiting while doing the work. The crew brought everything they thought they might need, including a spare material transfer vehicle, paver and roller, so they wouldn’t have to wait for anything. Instead of having four trucks running between the plant and the job, they had nine trucks. One truck left the plant every 15-20 minutes and then drove 1.5 hours to the site.

One truck blew a tire in transit, paving stopped briefly, and that mix had to be recycled. Otherwise, though, the process went smoothly. The lift was 7.5 inches thick before one roller pass with vibration took care of compaction. The crew monitored the work with Troxler 4640 nuclear gauges. Stevens had an extra double drum roller on-site in case it was necessary to use it, but the first roller pass was enough.

Staker Parson Materials & Construction paved on a Thursday and kept the paving closed to traffic until Sunday afternoon. (The paving had reached 100-120 degrees Fahrenheit two days after paving, but they wanted to be extra careful because they were doing something new.) Asphalt industry leaders came to watch. Attendees that day included regional directors, UDOT and Staker Parson staff, UAPA’s Reed Ryan, the Asphalt Institute’s Dave Johnson and others. The crew cored the pavement Friday and found the pavement’s average density was 97%. Anderson anticipated that result. He had designed for 1% but hoped for 3%-4% in the field.

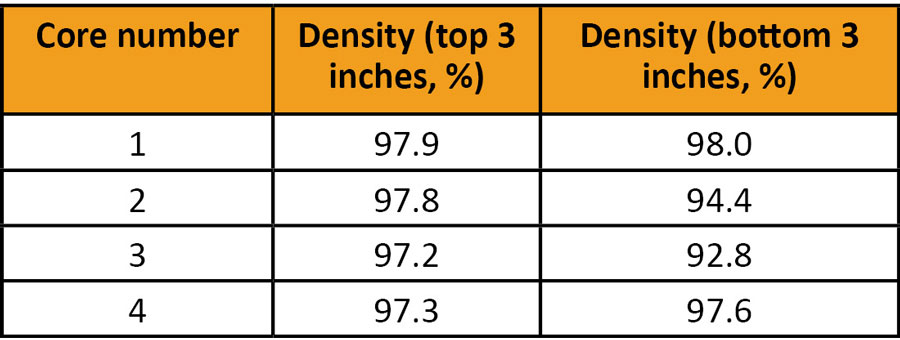

UDOT pulled four cores, one of which was at the point where paving had stopped after the truck blew a tire. That core had the lowest density. Despite the one sample with a lower density, Peterson was happy because the crew achieved full depth compaction and received 100% pay for gradation, binder content, and density. The compaction results are shown in the following graph.

Staker Parson Materials & Construction did an additional six-inch core on its own test strip. That one achieved 97% compaction.

Although using multiple asphalt layers can improve rideability and smoothness, their thick-lift test strip has not had any problems related to smoothness, though the crew did have to grind down the end joints. However, even though they had to grind the surface, they didn’t open the pavement to water.

Anderson visited the port of entry months after it was paved and found it was still free of ruts despite the high temperatures of summer 2021.

The port-of-entry project was successful, and it showcased the collaboration between UDOT and industry members and contractors. Anderson has found that many people are interested in the project because of its potential benefits. Production was faster, there was less inconvenience for drivers, and the project had cost savings. Because there was only one lift, there was no track coat. Also, one lift instead of two requires less traffic control and half the quality control. All those cost savings make it possible to spend more money on a high polymer mix.

Using a thick lift could also expand the paving season. November and April have cooler temperatures, which means paving during those months would speed up how fast the mat cools down after compaction.

Anderson’s next goal is laying a high-polymer, low void mix on a ten-mile road section and compacting it until it is eight inches thick. He suggests the results might be a perpetual pavement. Lifts of that thickness are similar to what can be done with concrete. If thick-lift asphalt can be placed and opened for use faster than concrete, and if the performance is equivalent to or better than concrete because joints could be eliminated, the industry benefits are obvious.

As Reed Ryan has pointed out, Marshall Mix Design has been used for 70 years, Superpave has been used for 30 years, and thick lifts might be the next step forward for the asphalt industry. Many people are interested, including DOTs for other states, legislators, and industry experts within Utah. Anderson expects to see more projects that use thick lifts with 1% air voids and a 76-34 binder.

UAPA’s leaders expect that, too, and they plan to continue being deeply involved. UAPA is valued when asphalt innovations are being discussed. That fact is a big benefit for all association members.